Rock, Snow, Water, Sky

From out of nowhere, two lives,

Sudden, like lightning, like budburst,

They explode together

Inevitable, like rock, like wind, they entwine,

Twin elements in some universe

Now, on the top of everything and the start of anything,

There is nothing

But the joining together.

And their love…

It is what must be

It is all that ever was.

I figure my wedding day was saved by a Nalgene bottle full of Tang.

We were in the second day of our ascent of Mt. Whitney, which, at fourteen and a half thousand feet of elevation, is the tallest peak in the lower forty-eight. It had sounded like a good idea at the time—we liked the poetry of getting married on that summit—but by the previous night at Trail Camp, at only twelve thousand feet, we were already getting goofy from lack of oxygen. We were repeating ourselves, and finding routine tasks difficult. A freeze-dried, just-add-boiling-water dinner only barely came together.

And now it’s the morning of our wedding day, and we’re up in the freezing dark, stumbling around and cramming stuff into packs with numb fingers. The lake is a quarter mile away and the water is freezing cold, so, on my own wedding day, I blow off the idea of shaving. We have 1,600 vertical feet of climbing to do to reach Trail Crest, at 13,650 feet, the last pass before the final push to the summit, and we have to be there by ten o’clock. We have people to meet, including the man who will marry us. We drop it into low and start climbing.

The switchbacks are mind-numbing. There are ninety-seven of them (people have counted them), zig-zagging across the biggest featureless talus slope of my life, and I’ve known a lot of featureless talus slopes. We’re so high above treeline that the forests below us look like nothing more than smudges of green on the sprawling rock landscape. We are in an elemental world now: rock, snow, water and sky. The air gets thinner. We keep climbing.

By the time we get to the pass, Susan’s gait is trudging and has some stumbles in it, and she’s lost her sense of humor. A freezing wind is blasting through the two-mile high pass and she’s starting to shiver, but we have to stick around, because this was where the rest of the wedding party was going to come up from the other side and meet us, so I park her hunkering behind a rock, bundled up in her wedding parka, with sand and grit blowing past her face, and I mix up the bottle of Tang and put it in her hands. Twenty minutes later she’s smiling again, like the hard-ass I fell in love with.

-

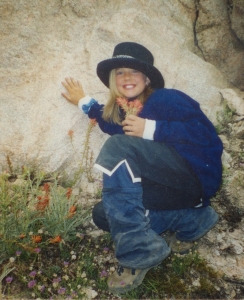

The hard-ass I fell in love with: Susan in front of the Whitney Skyline. We’ll be traversing that series of razorback ridges.

The plan was audacious but simple. We’d all meet at Trail Crest and hike to the summit together, and then after the ceremony the rest of the party would head back out to civilization, but Susan and I would disappear into the sunset and hike the John Muir Trail for our honeymoon. The John Muir Trail is a famous trail that runs up the spine of the Sierra Nevada mountains from Mount Whitney to Yosemite. Twenty days and 220 miles later, there would be a reception in Yosemite Valley, accessible to everyone including my dear old mother. (Susan’s dear old mother would be on the summit. She’s who Susan got her hard-ass gene from.)

You’d think that limiting your wedding party to people willing and able to climb Mt. Whitney would simplify it, but it hadn’t. For various reasons, the rest of the gang had had to leave a day earlier from a different trailhead, but the complications hadn’t ended there. My brother Byron’s daughter Brittany had gotten her trip trashed by the airlines and was arriving a whole day late. Last Susan and I had heard before we hit the trail, Byron still hadn’t laid hands on her and wasn’t sure when they’d start hiking. Byron was making the climb on a foot he’d shattered in a climbing accident not that many years before, but he absolutely refused not to be there. We’d gotten him ordained so he could perform the ceremony, so he was a pivotal piece of the whole plan. As things looked more and more uncertain with Britt, the Reverend Byron left a desperate message with his close friend Howie, an ultra-marathon runner who trots up Whitney for fun as a training exercise, begging him to show up in case Byron didn’t make it. I’m trying to picture that voice mail: “Howie! Quick! Get yourself ordained and be on Whitney at ten A.M. day after tomorrow! They’ll explain!”

Britt finally arrived, but without any of her luggage (including backpack, sleeping bag…) and in the end, she and Byron weren’t walking until late afternoon, with Britt entirely in borrowed clothes and gear, and they hiked into the night by flashlight, and somehow—I have no idea how—they managed to find the rest of the party where they’d camped for their first night.

And now, two mornings later, we look over from behind Susan’s rock, and there they all are, showing up not twenty minutes after we had, as if meeting at a restaurant for brunch. Susan’s mom is all smiles.

* * * *

The Reverend Byron is fond of saying, “In the end, all you have is the story.” We were determined to make our wedding a good story—we just weren’t quite sure how to do it. We had considered and rejected several ideas. We’re not religious, so the church thing was a non-starter. A country club, a picnic area, a winery, a beach—they were all a total snore to us. And besides, then what would we do for our honeymoon? Go to Disneyland? It was Susan who hit on Mt. Whitney. Then it immediately came to mind that not only would we be standing at the highest point in the lower forty-eight, we’d also be standing at the stepping-off point of the John Muir Trail. Oh, man, what a plan. We were hooked.

* * * *

We all drop our packs at Trail Crest and go light for the last two and a half miles of the ascent. It’s a spur trail, so we’d be coming back. Susan digs her wedding veil out of her pack and I put on my top hat, and the wedding procession begins. There are the two of us, the Reverend Byron, Susan’s parents Fred and Betty, both age 66, Susan’s niece Andrea, age 10, Byron’s daughter Britt, age 15, and Betty’s very close friend Sandy and her son David. Nine of us in all.

The Whitney Trail is not a technical climb, but trust me when I tell you that parts of it will make you dizzy, especially the last two miles, where it traverses a razor-back ridge top. The views are aerial, sweeping, vertiginous and surreal. To our right we can make out several different mountain ranges marching across the state of Nevada. To our left is the more verdant west slope of the Sierra Nevada Mountains, but we’re not seeing much lushness from up here, only continent-sized expanses of rock sweeping down and away from us into the distance, and then finally, way down there, a few smudges of green. But, true to my nature, my mind is also on the minutiae.

For there is a wildflower that grows up here, and it is called the sky pilot (Polemonium eximium). It grows only in the Sierras, and only above about twelve thousand feet. Most people will never see a sky pilot, and it’s one of the many rewards you get for climbing Mt. Whitney, or any of several other fairly serious peaks and passes in the Sierras. It was obvious to Susan and I early on that the sky pilot had to be our “wedding flower,” but we also knew that it couldn’t be. Not really, not physically. God only knows how protected those things are, and anyway, you’re not supposed to pick anything at all in a wilderness area. We had reconciled ourselves to enjoying the sky pilots only with our eyes.

But we hadn’t told the nieces that.

Andi and Britt hit the summit before anyone else, chose the spot, built an altar out of rocks, and then ran gleefully around gathering great armloads of sky pilots, decking the altar out with them, and creating a small bouquet for the bride to hold, tied together with nylon line. I trudged up and stood staring at the spectacle. I was mortified, but a smile was starting to grow across my face. Okay, I said to myself, this was meant to be. No way am I raining on Andi and Britt’s parade. The dirty coppers can take me away in cuffs when I reach Yosemite Valley if they want, but right now, I’m shutting up and getting married among all these sky pilots.

Byron’s service was wonderful, starting with congratulating us on our choice of cathedral and ending with “Please tell me you have the rings.” It took ten or fifteen minutes.

But actually, truth be told, we had had a fallback ceremony in mind, Whitney being Whitney. In case someone had altitude sickness, or a lightning storm was threatening, or it was freezing cold and blasting wind and someone was getting hypothermic, or for any other reason we needed to get the hell down, that ceremony would have gone something like this:

“Do you take—”

“YES!”

“Awright, we’re outa here!”

As it happened, though, several people experienced low points on the way up, but on the summit, everyone felt great and enjoyed the ceremony. After it was over, another scene unfolded involving Andi, Britt and the sky pilots.

“You gotta throw the bouquet,” they said.

And I’m thinking, You know, I hadn’t wanted this in our ceremony. That whole throwing the bouquet thing is an extremely sexist custom…

“You gotta throw the bouquet!” they repeated.

…I mean, it’s like, of course every unmarried girl in the audience wants to get married…

“You gotta throw the bouquet!”

…and of course their highest ambition in life is not to invent a vaccine or drive race cars, nooo, it’s to find a man…

“You gotta throw the bouquet!”

…but you know what? Andi and Britt are girls, for God’s sake, and they want us to throw the bouquet. For the second time that morning I told my brain to shut up, and Susan turned her back to them, and hefted the tiny contrivance of sky pilots and nylon line that Andi and Britt had so lovingly made for her.

What happened next was too perfect for words. Susan lofted it ten feet upward, and then a capricious gust of wind took that bouquet and whisked it right over the edge of the 3,000-foot vertical east face of Mt. Whitney. That thing is probably still falling. The girls were in hot pursuit, of course, leaping after it with great energy and athleticism, while the rest of us hollered, “STOP! STOP!”

They didn’t actually get that close to the edge, which was a good forty feet from us.

We hollered anyway.

* * * *

There was a forest fire somewhere. A big one. The sky was becoming a pall of brown-orange, and the sun was weakening and changing color, making the gusting wind seem more ominous somehow. Susan and I still had five or six miles to go, and the wedding party still faced eleven and a half to get out to the Whitney Portal trailhead. The top is only halfway there, goes the old mountaineering adage—it was time to get down. By the time we were approaching Trail Crest again, ash was falling on us and the air was a little difficult to breathe. People were hacking and walking around with bandanas over their faces. We gave Susan’s parents the keys to our pickup. Andi took my top hat. We exchanged many hugs and tearful good-byes, and then the wedding party dropped east off the mountain toward civilization, and Susan and I dropped west, onto the John Muir Trail. Neither party can see the valley they’re dropping into for the smoke.

The wedding party would not get out till well after dark. Everyone—including Andi, at age ten—had put in an 17-mile day. When they got to the town of Lone Pine, everyone had heard of the ten-year-old who summited Whitney. Byron and Britt got out just after the tiny restaurant at the trailhead closed, and had to share a single pack of ramen before sacking out in the back of his pickup. They agreed it was the best meal in the history of egg noodles. The next day Byron couldn’t even get around with a cane. He calls the whole experience “The best of times.”

Susan and I had been planning on camping at Guitar Lake but kept going to see if we could lose the smoke. We were dreaming. For the next week the smoke would come and go as it pleased, and rumors abounded among the hikers about where the fire was. We finally gave up and pitched camp. Our wedding night was, I’ll just say, subdued.

* * * *

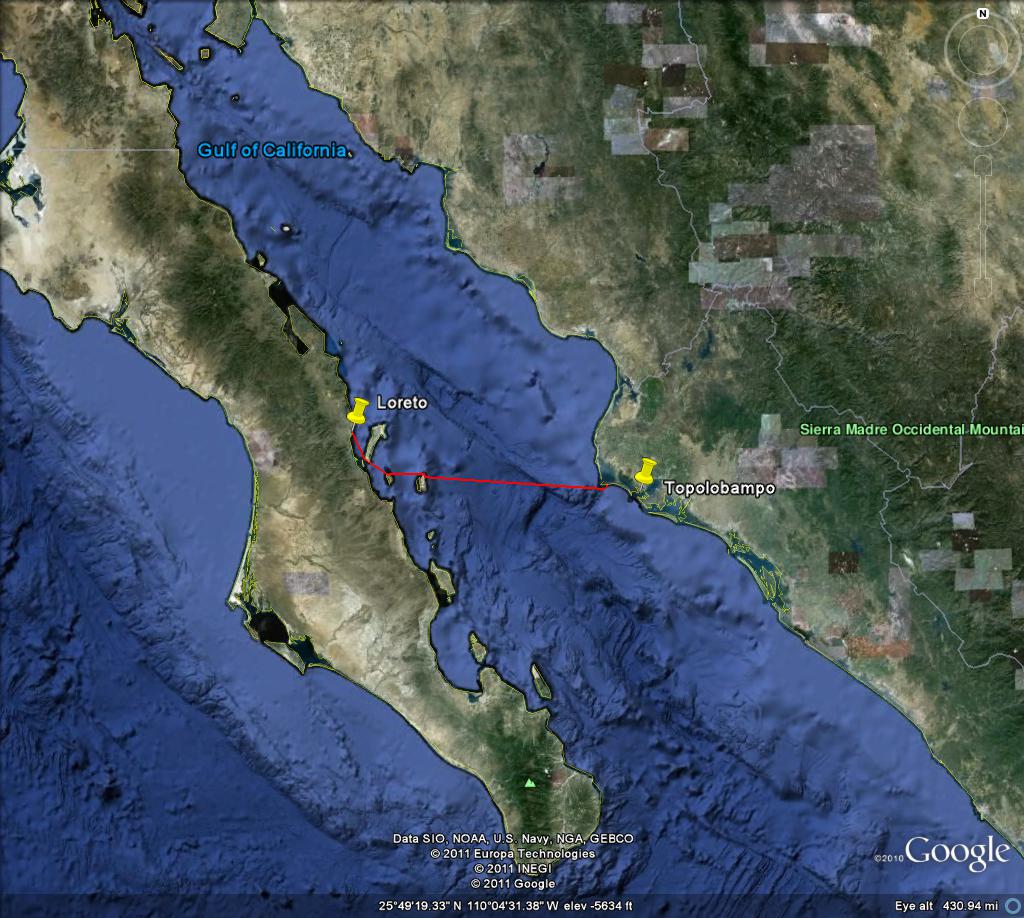

And so, by the power vested in Byron, we were married. The following eighteen days of honeymoon were the second-hardest thing I’ve ever done in my life. (The first was the Sea of Cortez crossing, though I’ll note that even that was over in two days). But although it was one of the hardest, it was also hands-down the greatest. I will never forget it. I will never forget the unending trail, the heartbreaking views, the endless walking, and the hours, miles and days spent above treeline with nothing but rock, snow, water, sky, and Susan.

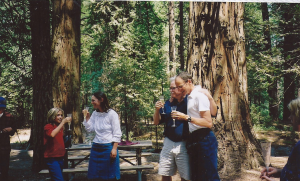

My older brother Gary gave the most beautiful toast in the history of wedding toasts, there at the reception on the banks of the Merced River in Yosemite Valley. Then he traded cars with Susan and I for logistical reasons, so it was his Jeep Cherokee that got its door folded back by a bear in the parking lot of the Ahwahnee Hotel because I left the top of the wedding cake in it.

All that was twelve years ago. I could have postponed writing this for a little longer, but I always figure there’s no time like the present. Andi and Britt are both grown now, and Andi got the hard-ass gene too. She just won a bodybuilding competition. And just so you know, Britt got one from somewhere as well (not hard to imagine where)—she’s a warrior, and bravely serves the country I love. Fred and Betty are seventy-eight now. Betty went through hip-replacement surgery a year ago, and she still hikes, and so does Fred.

And that’s how I married Susan.

I think it ended up being a pretty good story.