My nephew Ryan has my blood in his veins. He’s an obsessed nature lover with a sense of curiosity that won’t leave him alone. He captured this photograph near Bonny Doon, in central California, where he was working for an environmental landscaping outfit restoring an old quarry which, they say, largely rebuilt the city of San Francisco after the 1906 quake. He did what any of my relatives do when they see something weird in the natural world: He emailed it to me.

I knew immediately what it was, because it’s a childhood memory for me. My friend and I were scuffing around in my backyard one day when I was maybe ten, and I remember that the fence with our neighbor in one place seemed like it was about twenty feet tall, and it was completely covered with honeysuckle vines, just a wall of lush foliage and fragrant blossoms several feet thick, and at one point my buddy said, “Hey, come look!”

I can’t even remember which childhood friend this was, but I vividly remember what he showed me: He parted the vines before our faces, and we were looking at a solid wall of honeybees.

It’s a behavior called swarming, and it’s how hives make new hives. The queen bee defects with maybe sixty percent of the whole hive, and heads out to establish a new republic. It’s pretty much on a timer: After two years of non-stop effort laying worker bee eggs, she lays a few eggs in some of the larger queen bee honeycomb cells and then blows town with half the troops. It’s interesting to me that it’s the existing, proven queen that ventures out with the swarm, not one of the new ones. It puts both hives at risk in the end.

The swarm only moves a little way at first, sometimes only a few yards. (That’s worth remembering—when you see a swarm, there’s a hive nearby, and though the swarm is not aggressive because they have no young to protect, that’s not true of the hive.) In their new, nearby location, the swarm aggregates in a mob around the queen, protecting her and staging themselves for the move.

The next thing that happens is that somewhere between twenty and fifty scout bees fly out looking for a new nest site. They are from the ranks of the experienced forager bees, and they know the landscape. They need to find a new site pretty quickly and get a hive working—they’re running on nothing but the food in their bellies, and the queen was starved by her nurse bees prior to the move so that she’d be able to fly. The site must meet many criteria—it must be a cavity protected from the elements, big enough for the hive, warmed by the sun but not too much, and free of ants. They’ll fly as far as a kilometer or two looking for something that works. When they come back, they dance about it.

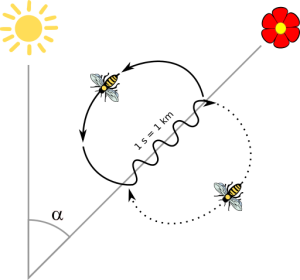

No, really, that’s what they do. There’s a saying that talking about art is like dancing about architecture, but bees actually do dance about architecture. It’s called a “waggle dance,” and it’s how bees describe to each other the location of something like a food source. They run up the wall of the hive waggling their posterior back and forth. The length in time of the waggle run indicates the distance, and the direction of the run indicates the direction of the thing relative to the sun. A Nobel Laureate named Karl von Frisch figured this out. Straight up the vertical honeycombed wall means straight toward the sun, twenty degrees to the right of vertical means twenty degrees to the right of the sun. And if it’s been a couple of hours since she returned to the hive, she corrects for the intervening movement of the sun. I’m not making this up.

-

The Waggle Dance

By Own work[CC BY-SA 2.5], via Wikimedia CommonsIn the case of a swarm, though, they add another dimension to the choreography: The more excitedly the bee dances, the better the site met the criteria.

So they all come back, and everyone dances, and then some of the scouts will go back out and check out a couple of the sites promoted by the most excited dancers, and when they come back, they might start promoting that site as well, and others will go out and take a look. It is only when complete consensus is reached that the swarm flies off and moves into the new hive.

This process by which the swarm collectively decides on the site for a new hive is quite fascinating. Each bee follows only a fairly simple set of rules and cues, but the the problem that gets solved is a very complex one (an optimization problem). They are deciding between multiple options, and condidering multiple datapoints for each, and the problem gets solved very intelligently. It is what scientists call collective intelligence, and it’s studied by more than just naturalists. The whole becomes greater than the sum of its parts—it’s studied by computer scientists, industrial engineers, and anyone who has to make large numbers of people do something complex with only a few instructions. It might be the subject of my next article.

Meanwhile, back in the old hive, things might be a little rough. They’ve only got half the woman-power they used to have (worker bees are all female), and also, the newly-hatched queen bees are called “virgin queens,” and that’s exactly what they are—they are not capable of making babies and replenishing the workforce until they have sex, which takes place hundreds of feet aloft in an elaborate mating flight where she could easily get nailed by a predator and then the hive would collapse, because there is no backup queen. Though the departing queen laid several eggs in queen cells, queen bees do have stingers, and they’re used exclusively to kill rival queens as they pupate in their honeycomb cells. The sex is not particularly modest—the virgin queen will mate with from twelve to fifteen different drones, returning to the flights for several days, storing the sperm in an organ called a spermatheca, from which she will use it at will for the rest of her life, which can be from four to five years. She chooses which eggs to fertilize. Unfertilized eggs become drones, the only males in the hive. The fertilized ones all come out female and will be workers unless the worker bees pack the cell with a substance they manufacture called royal jelly, which will alter the way she develops and create a queen. So it’s actually the workers who are the queenmakers. They decide when a swarm is called for, or when the existing queen is weakening and needs to be replaced. They detect this because her pheromones start to get weak, and they will raise some new queens, and then kill her.

Worker bees don’t live as long, only a couple of months. But in that time they live a full life, going through several different careers, starting out doing menial cleaning work or tending to the young, then venturing out with experienced foragers on orientation flights, learning the landscape and becoming valuable breadwinners, bringing pollen and nectar back to feed the hive. In their sunset weeks, they are put to work guarding the hive, and are the ones who will attack and sting an intruder, leaving their barbed stinger and a handful of abdominal organs in the adversary and dying themselves. They have become expendable warriors.

Well, to take us back to the nineteen-sixties and finish the childhood story, my folks called a beekeeper out, and when he got the swarm into a hive box I asked if I could keep it. My parents, being my parents, said, “Sure!” They were always very supportive of my natural obsessions, so for a year or so I became a beekeeper. It put everyone in the family to some trouble. My mom at one point got swarmed and was laid up in bed for several days. Bees actually have a very powerful venom, and if you get enough stings it can be pretty brutal. Foraging honeybees seldom sting unless roughly handled, and it will be the only sting you get. (My first bee sting—a traumatic, earlier childhood memory—was when one got tangled in my hair and I reached up to see what was going on.) But if you get stung near the hive you’ll find out that when they sting they also release a pheromone that sets off any other bees nearby, and you can get swarmed. They’ve got an extremely accute olfactory, and the pheromone is persistent, and even if you’re lucky enough to be near some water you can dive into, when you come back up they’ll resume the attack.

My beekeeper career was not terribly successful. The hive lost its queen somehow, and Gary, always the supportive and helpful brother, would assist me in taking the top off the bee box and lifting out the vertical racks of honeycomb (massed with bees) one after another, looking hopefully for queen bee cells that might hold a pupating new queen. Our folks didn’t have a ton of money and had only sprung for one beekeeper hood, so Gary would wear a pair of toy aviator goggles from a dime store, and one time a bee managed to get up underneath one of the lenses and was frantically buzzing around right in front of his eyeball. I can’t remember whether he actually got stung (Gary, do you recall?), but the dance he did as he ripped the goggles from his head transcended the boundary between self-preservation and art.

In the end, the hive perished, and my family set out on the path toward physical and emotional recovery.

Now you know.

Fascinating, Randy! Looking forward to more of your writings.

Thanks, Hari! Great to hear your voice! How is India treating you?