The author discovers that crossing the Sea of Cortez by ocean kayak is about faith, commitment–and pain

Originally published in Sea Kayaker Magazine, February 1997 edition.

Copyright © 1997 Randy Fry.

“So you’re going to island-hop through the Midriff chain, right?”

My girlfriend Susan sets her shot glass down and reacquires my distracted gaze.

“Right?”

“Well, actually . . .”

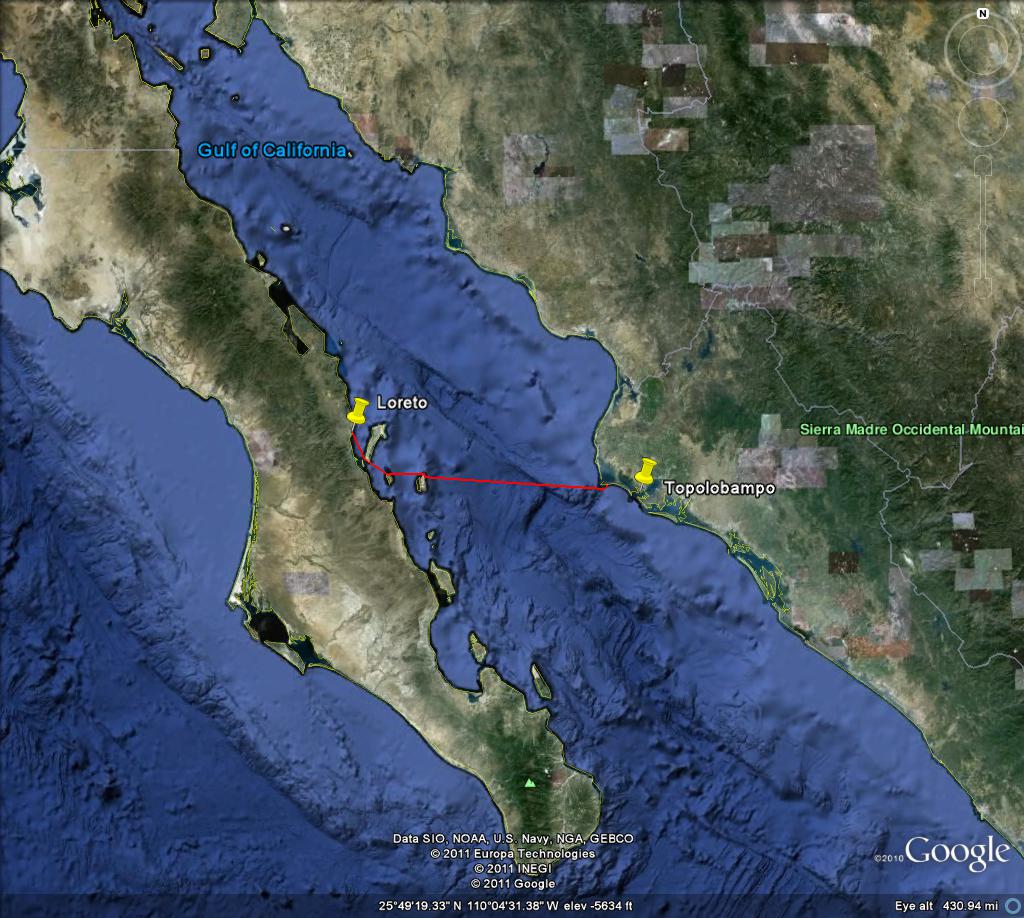

Actually, what was sort of materializing in the air here was an open-water crossing of the Sea of Cortez, from Loreto in Baja California to Topolobampo on the mainland of Mexico. There would, to offer scant comfort, be two initial island hops–from Loreto 24 miles to Isla Monserratt, and then out 17 more to Isla Santa Catalina–but only to get our footing for what my mind was already calling The Big One: a single open-water crossing of 73 nautical miles to the mainland, which we expected to take a day, a night, and another day of steady paddling on a sea known for sudden change. I am watching somewhat helplessly as the plan takes possession of my insides, and I am captivated, I am inspired, I am . . .well, terrified. All day I’d been trying to come to terms with the most unnerving part of it: I’d been invited.

Fortunately, Susan shares my dysfunctional attraction to marathons, crossings and pointless pain in general, so I don’t have to explain to her why I want this crossing more than I want world peace, which is nice, since I’ve never in my life been able to get it across to anyone who doesn’t already understand. (“Because it’s there” stopped working for me when I read that climber George Mallory later died on the mountain under discussion.) Was it to learn something about myself? That can be a mixed-as-hell blessing: I was already discovering that my greatest fear was not that I would die at sea; it was that I would be the weakest paddler in the group. Did I want the crossing for whatever notoriety it might bring? Not likely–far bigger things have been done in ocean kayaks. But then, those expeditions were all very different from this one: I wasn’t on them.

Again I draw the familiar blank. I would know after the crossing why I was on the crossing. I look up, at a loss, but I recognize that grin on Susan’s face, and it means she recognizes that gleam in my eye. Susan knows what’s got into me. And I envy her knowledge.

There wouldn’t be much time for thought in my immediate future, though. Things start to move fast, and four weeks later the trip has miraculously come together and I find myself loading a pair of double kayaks on a beach in Loreto with the three complete strangers who have taken a chance on a complete stranger. Who are these people? I am asking myself. And what possessed me to trust them with my life? What possessed them to trust me? Do they even know what they’re doing? I’ve long considered group dynamics to be the deadliest natural force on the water. Will it spin out of control, as I’ve seen it do too many times before?

We launch and head south-southeast, swinging around the southern tip of Isla Carmen and out toward Isla Monserratt. It’s my first time on the Cortez, and I see with fresh eyes the arid colors of the Baja mountains leaping in understated splendor thousands of feet out of the water, and the frigate birds by themselves are enough to make my heart ache, with their effortless flight and elegant scissor-tailed profiles, but I’m not enchanted, I’m obsessed. I’m a man on a mission. I may be clueless as to its purpose, but that’s never cooled my fires a bit–nothing important I’ve ever done in my life has had a rational purpose. This morning I have enough ambitions and anxieties in me to fill the burly breast of a conquistador. I am Hernando Cortez with a GPS.

We camp on Monserratt, we camp on Santa Catalina, and during the crossings between we are shaking it down, knocking the bugs out and making it work. We shuffle and reshuffle the pairings in the boats, leveling out the paddling strengths. We get to know my shiny new Global Positioning System, a life-saving little magic box (which could be dropped in the drink or killed with a paddle blade at any moment). We practice with it, discovering a precocity for the kinds of programming errors that could give us a whole new trip. We practice with our drogue and our sponsons, pre-rigging them on our decks in case we have to sit out a serious blow. Our plan is for one boat to deploy a drogue from its bow, while the other tethers to its stern. This should keep us both turned into the weather, and the boat in the rear, which will tend more to fishtail back and forth, will have the added option of the sponsons. But we are disturbed by the need to raft up to accomplish the whole thing–all gallantry aside, we would prefer not to come anywhere near each other in seas nasty enough to require it. We finally work out a system that involves the forward boat heaving a throw-rope, and the other clipping a bow painter to it with a carabiner, with all knots slipped for quick release. We are happy with the system–it comes together in moments. Famous last words run through our heads: it should work.

And we are getting to know each other. Kim Burt, Tony Prendergast and Steve Wheeler all work for Colorado Outward Bound School, running kayaking trips out of Loreto through the winter. For them, this crossing is an off-hours lark to keep the boredom away. I find them to be a lionhearted group, in a peculiar, lighthearted way. It is not a reckless or rebellious fortitude, this dauntless spirit of theirs–they simply lack the usual bigotry about what can and cannot be done. They are cheerful, optimistic, skilled, even cautious in their way–and absolutely intrepid. They have been running wilderness programs together for years and are like brothers and sister. They are completely gender-liberated in all the completely incorrect ways. They make lewd comments, laugh a lot, and use unconscionable terms like “girls” and “boys” that in my vocabulary have long been grounds for political imprisonment. I find it refreshing, this style of enlightenment that does not involve mutual androgyny. Nervous about being the unknown quantity in the group, their remarkable three-way relationship goes a long way toward relaxing me.

And always, the talk turns to the weather. For these are the waters haunted by the monster called El Norte: north winds that come howling out of nowhere, they say, and blow for, oh, anywhere from four hours to nine days. In Mexico, marine weather broadcasts are just a small, wishful aside to the Great American Dream. We are looking at the sky and making them up ourselves, but no one can predict a 30-hour weather window in Baja. Anything could happen. And anything’s okay with me, I tell myself–I’ve always wanted to see Guatemala anyway. What actually bothers me more than the lurking Nortes is the fact that on both of the preliminary crossings we’d been fighting an uncharacteristic southeast wind of 10 to 15 knots. We know that with even that much against us, we won’t launch for the mainland.

That final night on the beach on Santa Catalina, I awaken often, aware of every breeze that crosses my sleeping bag, and its strength and direction.

But finally, it is proven to me that at least some of the things they taught me in elementary school were true, and the planet is indeed rotating–Saturday morning dawns bright and foreboding, and the sea is already whitecapping, but the wind has changed: it is from the north, and we hold a small hope that it might be wrapping around the island, and in open water will swing around to maybe a hair behind us, and be of a little help. Right now it looks like ten to fifteen knots, judging by the water, but it’s early for a north wind–will it change from north to Norte? We stand in the wet sand facing 73 miles of open water, and feeling that slight vacuum that exists when a great moment is finally at hand. To the east, there is not a hint of land. We talk, invent some more theories about the weather, establish decision-making procedures, elect Kim leader, and the discussions have none of the cautious tones that characterized earlier talks on earlier beaches. The group synergy is good. The day is here. The crossing is go.

* * * *

“One: Get on the water. Two: Keep moving.” This is how I describe to people the secret of making a long crossing. This group seems to understand it, and we are making steady progress on our first day, breaking only every couple hours, crawling along our course, reeling in the opening miles. By the rule of thumb that one foot of elevation is lost below the horizon for each mile of distance, the mountains of Baja should in theory be visible even from the mainland, but there is enough light haze on this day that by late afternoon we are out of sight of all land, and our universe consists solely of sea, sky, and descending sun. It is part of the character of a long crossing that it offers little material for the descriptive writer, or, for that matter, for the bored paddler. For endeavors so profound, crossings can be remarkably unremarkable. But only externally–for there is a rhythm, a heartbeat to a long crossing, which back-to-back islands would preclude. As the empty hours move slowly by, I begin to compose entries for the personal journal I left at home. The rhythm, I write, is the heartbeat of the crossing–it makes it move, and gives it life. The steady flashing of tiny paddle blades, alone on thousands of miles of water, give the sun reason to glint, give our bodies reason to move. The rhythm is time combined with space–paddle strokes combined with water.

The seas have indeed come around to a gratifying ten or so degrees behind our beams, and they are small, ranging from one to three feet as the wind comes and goes. As six-o’clock approaches, we tie off to the drogue and break for a cold dinner, and I take a reading on the GPS. Neither the “weatherproof” GPS nor the “waterproof” radio bag I bought to hold it have performed as advertised, and condensation is already appearing in the display window. I find this development pretty sobering, and it reconfirms my belief that any technological gadgetry carries an inherent risk in a wilderness situation. So far, though, it’s still working–in eight hours of paddling, we’ve covered twenty miles of our 73-mile course, and we’re beginning to realize that most of our bail-out options are ceasing to make a lot of sense. We are committed. The crossing will succeed or fail.

Whatever “fail” may mean on this crazy trip–we have yet to see another boat, and our hand-held VHF radios have a reach of maybe three miles.

We are keeping to our course well, having only been blown a few miles south of our intended line, a deviation which we decide not to bother ourselves correcting. Tony is proving to have an uncanny knack for estimating ferry angles in the wind, and we are slipping no further. Ultimately, of course, it would be difficult to miss our objective–paddle east and you’re pretty likely to hit the North American continent–but what does happen south of Topolobampo is that the coastline cuts steeply eastward, and our crossing begins to swiftly pile on additional miles. We are very, very interested in making that not happen.

With a collective sigh, we stow our food, seal our skirts, and start moving again, paddling toward an invisible mainland, and toward a long, long night. The miles begin again to crawl beneath us. The hours begin again to stretch out and out across the water before us.

* * * *

Early evening. The sun is low behind us, and the absence of landmarks is posing problems not just for the undisciplined mind, but also for the navigator, who, in the absence of even the stray distinguishable cloud to sight upon, must paddle with eyes glued to a wildly pitching compass card. We have been trading off the tedious task when we break, and right now it is my own unfortunate eyeballs that are beginning to slip all mooring and roll around loosely in my skull. Finally, I am saved by one of my favorite miracles of nature. On the distant horizon, at a bearing of exactly 081° magnetic–which is to say exactly our heading–an amazing event occurs: the moon rises. Like an answer to a prayer, the three-quarters globe floats luminously out of the water, leaving us no longer alone to face the coming night. Its presence is absolute, immediate–it has never seemed so real to me. It is the closest thing to us; closer, certainly, than the mainland. With spirits lifted, we paddle toward it as if toward a lighthouse. I feel good. I decide that I’m holding up well. I can make it through this night.

Three hours later I’m nodding off with my arms still moving. It’s dark, but the moon is high in a clear and starry sky. I find myself wondering what would happen if I were to truly fall asleep. Would I slump over and capsize us? Would I lose my paddle? I cling to a wisdom I have gleaned from long endurance events: you will feel good, and then you will feel bad, and then you will feel good again….it will come back. Ultimately, though, it’s an academic question: crossings are crossings, and this is the magic of them. There are no beaches, there is no bailout. Quitting is not an option. Crossings are about committing. I splash some water in my face and paddle on. We’re now thirty-two miles out, an average of two and one-half knots. It’s roughly what we expected, but I’m having major problems with the figure. An hour of paddling and two and a half miles go by? Out of seventy-three? Who the hell did I think I was to come off the wall and attempt a thing like this? Clearly, my spirits are hitting a low point. In my current state of mind, I’m not entirely convinced that the mainland will even be there. Here amid all this water and all these stars, our yearned-for destination seems like nothing more than a wispy academic construct, assembled for our own comfort from a careless heap of photocopied nautical charts on a kitchen table in Loreto. The crossing is also about faith, I remind myself. You must know, somehow, that the mainland will be there.

-

Steve and Tony as we attempt a short nap–whoever wrote that one can sleep in a kayak must have been more tired that we

At midnight we concede to the fatigue and tie off to the drogue for an extended break. We squirm down into our cockpits to attempt a short nap, but whoever wrote that one can sleep in a kayak must have been more tired than we, though that’s a difficult state to picture at this point in our lives. Forty-five minutes later we give up and are moving again. I break out some chocolate-covered espresso beans, and they’re a big hit. They churn up our stomachs and make our mouths taste like cigarette butts, but they do a serious trick. Whales blow somewhere very near, and all we can see is some moonlit roiling of the surface waters, but they sound very large, possibly fin whales, or blues. Comet Hyakutake is in the northern sky above us, adding poetry to our expedition, and an historical locus.

But what I would remember most about this night would be the three hours between moonset and sunrise, when we are plunged into darkness only to see the water ignite with bioluminescence. The seas have kicked up to five and six feet, bringing us undeniably awake, and every bite of a paddle blade and plunge of a bow sends out a spray of silver-blue sequins. They lie burning like icy embers on our deck, and on the shoulders of Kim’s paddling jacket in front of me. They spangle the breaking crests of black waves and merge imperceptibly into the phantasm of Baja stars, with no visible transition between the two. Stars above and stars below–at once unnerved and enchanted, we surf through the cosmos with comet Hyakutake, dreaming of a sunrise far away on a planet called Earth.

Finally the eastern sky before us starts to brighten, and we tie off to the drogue again for an extended break. Tony drops over the side for a dip, and Kim does likewise and pulls herself up the drogue line to him, only to learn that he is in the water to answer one of the more serious calls of nature. Kim, of course, laughs uproariously, teases him loudly, but does beat a retreat back down the line to our boat. A minute later, Steve sights a fin cutting the surface, and calls out to him. What follows is one of the most miraculous re-entries I have ever witnessed in my life. It resembles most closely a trained seal–or perhaps a nike missile–rocketing vertically out of the water, and in no more than a heartbeat Tony is sprawled crosswise across his deck with not a single hand or foot touching the surface–and with his shorts around his knees. That moment while Tony was displayed to the sky would be the only time I saw this group exercise any restraint whatsoever in their unmerciful teasing of one another. Looking back, Steve says he’s pretty sure he saw spines in the dorsal fin, suggesting it was a sailfish, and not a shark. Probably.

We throw down some cold breakfast, stow the drogue, and paddle resolutely on, into what would be the longest day of my life.

At 7:10 Kim calls out that she sees land. It is the merest hazy brown line on the horizon, and it seems achingly distant, but it uplifts us, and we paddle with new resolve. Land! We are in sight of land!

Ten minutes later it rises into the sky, proving to be only low clouds.

At seven-thirty, we really do sight land. It seems no closer nor tangible than the cloud bank had, but it has the decency to stay put, and we begin to place our faith in it. The daylight has awakened our circadian rhythms, and with our objective in view, however distantly, our mood rises. We are beginning to feel, really feel in our hearts, that we might make it. We paddle on, and the time is absolutely crawling.

The time, I mentally write in my journal, is thin, elongated, empty. The time is depleted of objects and events to give it shape, and it stretches with impossible elasticity all the way from Loreto to the mainland, strung tenuously like gossamer across the water between the sparsest scatter of occurrences. The time leaves us with nothing but ourselves, while the crossing leaves our selves with nothing but the crossing….

We probably have eight hours still to go. We keep paddling.

* * * *

Ten o’clock in the morning. I have never in my life been in this much pain and kept going. My torso feels like it is wrapped in an incandescent sheath from armpits to hips, and it lights up with every paddle stroke. The deltoid muscles on the tops of my shoulders–the hold-your-paddle-in-the-air muscles–are on fire, and though I am confident of my endurance strength, I have a great fear of muscle failure. Only one has to fail, I figure. And even beneath the torments of the flesh lies another, more enduring and general exhaustion. Between each stroke it is a conscious effort not to drop my arms and stop. A mental image of my own torso is drifting around in my mind, and it is a scarecrow-like specter of skin stretched across ribs, thin and wavering, lacking the substance to be doing anything close to what I’m asking of it. Back in the middle of the night I was at the point at which I normally say I have nothing left. How long ago was that? Ten hours? Twelve? All things considered, I am amazed to the point of immodesty at the strength that somehow remains in my stroke. The miraculous biological machine is holding up. Still, somehow, my blade bites water. Still, somehow, my body lights with strength from somewhere. I have no idea where I am finding it, but I know why I am. I am finding it because this is a crossing. I am finding it because I have no choice. Friends had asked me why we weren’t arranging for a support boat, and now I know. Because the crossing would fail. Were there any other option whatsoever right now, I would summarily quit.

The pain, I write as one stroke follows another, is the hard spot inside the crossing that gives it substance, distinguishes it from an amusement park ride. The pain is the other half of some universal duality; it is the opposing force, the reason crossings are not done, the reason we’re not sure this one can be. The pain is the spiritual airlift that removes us forcefully, bodily, from our complicated existences and gives us the exalted gift of thirty whole hours of simplicity. Everything else, even friends and loved ones, drops away, and for thirty hours there is only one care, only one goal. The pain is the greatest pleasure of the crossing.

Still the winds are no more than 15 knots from the northwest, the seas smaller than six feet. At noon we take a short break, and the GPS (still working!) tells us we’re twelve miles from our landing site at Punta Arena. Four or five hours, probably. We consider breaking out the drogue and taking an hour’s rest. My body craves it in a way it’s never before craved a thing, but I rally my resolve and argue for pushing on while our luck with the weather is holding so miraculously. We do have a concern about encountering offshore winds as we approach the coast, and if they’re too tough to paddle into, we’d be in a pretty bad spot. We certainly can’t turn around and head back.

It is partly the strength within each of us, and partly the group support between us, that is getting us through these last hours. Kim, Tony and Steve, with their years of joint wilderness experience, seem to have evolved a group response to tough times: they get more gregarious as the exhaustion mounts. It’s a nice trick, and I congratulate myself again for trusting the common friend who recommended us to each other. Kim, in an inspiring display of group leadership, pulls us assertively into word games and team building exercises, drawing from a deep bag of Outward Bound tricks. We each share the three historical people we would most like to meet and talk with (Kim goes straight for the hard answers, deciding on Jesus Christ, Buddha, and Mahatma Gandhi). We each share our favorite sexual fantasy (talk to Tony for a really good one). Tony and Steve (a.k.a. The Boys) spontaneously start singing old Eagles tunes. We all join in, and an hour of something resembling drunken caterwauling goes by, during which not a single pelagic bird comes anywhere near. I hearken back to my singer-songwriter days and amaze myself by remembering all the words to American Pie, and then pulling out some Arlo Guthrie, some Loggins & Messina, and we finish the set with a medley of old Beatles tunes. It distracts us. It helps. Anything helps.

The mainland is coming no closer and coming no closer and coming no closer. I am convinced that our exhausted bodies are being outdistanced by continental drift. But I feel a communal craving for the fervently-imagined beach on the distant shore, and, amazingly, we pick up the pace. “The end always comes,” I hear Susan advising me. “You will think that it never will, but it always does.” And her advice is good–finally, incredibly, we are picking our way, with the help of some advice from a local fisherman in a small “panga,” through an extraordinary zone of currents and converging, haystacking systems of swells, to a deserted white sand beach on the south side of Punta Arena. As our bows grind up onto the sand, I feel only an odd distraction and emptiness. There is no welcoming contingent, no banners or brass bands. Just us, our boats, our paddles, and our own small inner voices saying “You did it! Listen! Drop that drybag and listen! You did it!”

The landing, I write to myself, is that slightly empty, is-that-all-there-is feeling of looking around the empty mainland beach and wondering why the sun hasn’t halted its heavenly circuit in commemoration. The landing is a self-conscious groping for a scripted profundity. The landing is distraction: wobbly legs, necessary chores, reeking cockpits, gear coming out of hatches, bodies managing even now to carry on–but somewhere, in some nearly subconscious and nearly inaudible subcurrent of awareness there is . . .

. . . sand between the toes!